First Reading

Genesis 17:1–7, 15-16 (Omitted verses included in italics)

When Abram was ninety-nine years old the LORD appeared to Abram and said to him, “I am God Almighty; walk before me, and be blameless, that I may make my covenant between me and you, and may multiply you greatly.” Then Abram fell on his face. And God said to him, “Behold, my covenant is with you, and you shall be the father of a multitude of nations. No longer shall your name be called Abram, but your name shall be Abraham, for I have made you the father of a multitude of nations. I will make you exceedingly fruitful, and I will make you into nations, and kings shall come from you. And I will establish my covenant between me and you and your offspring after you throughout their generations for an everlasting covenant, to be God to you and to your offspring after you. And I will give to you and to your offspring after you the land of your sojournings, all the land of Canaan, for an everlasting possession, and I will be their God.”

And God said to Abraham, “As for you, you shall keep my covenant, you and your offspring after you throughout their generations. This is my covenant, which you shall keep, between me and you and your offspring after you: Every male among you shall be circumcised. You shall be circumcised in the flesh of your foreskins, and it shall be a sign of the covenant between me and you. He who is eight days old among you shall be circumcised. Every male throughout your generations, whether born in your house or bought with your money from any foreigner who is not of your offspring, both he who is born in your house and he who is bought with your money, shall surely be circumcised. So shall my covenant be in your flesh an everlasting covenant. Any uncircumcised male who is not circumcised in the flesh of his foreskin shall be cut off from his people; he has broken my covenant.”

And God said to Abraham, “As for Sarai your wife, you shall not call her name Sarai, but Sarah shall be her name. I will bless her, and moreover, I will give you a son by her. I will bless her, and she shall become nations; kings of peoples shall come from her.” (ESV)

Second Reading

Romans 4:13–25

For the promise to Abraham and his offspring that he would be heir of the world did not come through the law but through the righteousness of faith. For if it is the adherents of the law who are to be the heirs, faith is null and the promise is void. For the law brings wrath, but where there is no law there is no transgression.

That is why it depends on faith, in order that the promise may rest on grace and be guaranteed to all his offspring—not only to the adherent of the law but also to the one who shares the faith of Abraham, who is the father of us all, as it is written, “I have made you the father of many nations”—in the presence of the God in whom he believed, who gives life to the dead and calls into existence the things that do not exist. In hope he believed against hope, that he should become the father of many nations, as he had been told, “So shall your offspring be.” He did not weaken in faith when he considered his own body, which was as good as dead (since he was about a hundred years old), or when he considered the barrenness of Sarah’s womb. No unbelief made him waver concerning the promise of God, but he grew strong in his faith as he gave glory to God, fully convinced that God was able to do what he had promised. That is why his faith was “counted to him as righteousness.” But the words “it was counted to him” were not written for his sake alone, but for ours also. It will be counted to us who believe in him who raised from the dead Jesus our Lord, who was delivered up for our trespasses and raised for our justification. (ESV)

Gospel Text

Mark 8:31–38

And he began to teach them that the Son of Man must suffer many things and be rejected by the elders and the chief priests and the scribes and be killed, and after three days rise again. And he said this plainly. And Peter took him aside and began to rebuke him. But turning and seeing his disciples, he rebuked Peter and said, “Get behind me, Satan! For you are not setting your mind on the things of God, but on the things of man.”

And calling the crowd to him with his disciples, he said to them, “If anyone would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me. For whoever would save his life/soul will lose it, but whoever loses his life/soul for my sake and the gospel’s will save it. For what does it profit a man to gain the whole world and forfeit his life/soul? For what can a man give in return for his life/soul? For whoever is ashamed of me and of my words in this adulterous and sinful generation, of him will the Son of Man also be ashamed when he comes in the glory of his Father with the holy angels.” (ESV)

Comments and Questions for Discussion

First Reading

Last week I’m afraid I gave too little attention to the first of the covenants God made with humankind. The importance of the organizing principle of covenant in the Hebrew Scriptures would be difficult for me to overstate. Here in chapter 17 we find the second of the covenants that God establishes, this time with Abraham, that he would be “the father of a multitude of nations.” It is actually a repetition of the covenant given in chapter 15, with some expansion, but it is still the second occurrence of covenant as a guiding principle in the Bible.

This second iteration of the covenant with Abraham seems to me to prefigure the second giving of the covenant at Sinai. At Sinai, God gives the first tablets to Moses, but because of the people’s faithlessness, the tablets are broken. After Moses’ intercession they are given a second set of tablets, in spite of the fact they remain a “stiff-necked” people. God gives a covenant that They shall not break, no matter what the people do.

In the case of Abraham God promises a son and a multitude of descendents to him in chapter 15, but in chapter 16 Abraham’s faithlessness leads him to sire an heir through Hagar, bring great hardship on both her and her son Ishmael. Once again God re-establishes the covenant and this time adds a sign on Abraham’s part (the verses that were omitted). Circumcision shall be that sign, just as the keeping of Sabbath shall be the sign of the Sinai covenant. And as with God’s people at Sinai, the covenant shall remain no matter how often Abraham fails to walk before God and “be blameless.” (As he clearly does with Abimelech in chapter 20.)

This example that seems to prefigure the Sinai covenant seems also to be a repetition of the pattern that encloses the “primordial history” of Genesis 1-9. While there is no mention of “covenant” God gives a good Creation into the care of humankind. Because of human sin, this creation is ruined and God wipes it away in the Flood, but gives a second world to humanity in spite of the fact that the imagination of the human heart remains evil. A first relationship (that can be broken by sin) is indeed broken, but it is replaced by one that cannot be broken, no matter our faithlessness.

While studying for this Divergence I came across a fascinating article on the text of Genesis 17:14, which isn’t part of our reading for this week (though it’s in the verses that were left out). In it, Matthew Thiessen argues persuasively that the oldest version of the verse included “on the eighth day” as part of the circumcision requirement not to be cut off from God’s people. It’s a small thing, but his explanation of why it was possibly (probably?) left out by later redactors is that it was too harsh. It left no room for the child who was too weak to survive circumcision on the eighth day and made no room for proselytes who came to faith later in life. I know, a small thing, but I really enjoyed seeing the way that compassion had shaped the text over time. Should you care to read it, here’s a link.

Second Reading

Our reading from Romans this week involves a portion of Paul’s argument concerning the righteousness that comes “not only to the adherent of the law but also to the one who shares the faith of Abraham.” In this part of the chapter Paul harkens back to the promise given to Abraham, but not the one included in the lectionary for this Sunday. Rather, Paul refers back to the first promise in Genesis 15. It is in that chapter that Abraham’s faith in the promise is reckoned to him as righteousness.

We are all familiar with the phrase “by faith alone” that Luther drew from this passage. It is fundamental to Christian belief that righteousness comes through faith, the faith of Abraham, the faith of Jesus Christ. (For that is what Paul enjoins, not faith in Jesus Christ, but having the faith of Jesus Christ.) I don’t think that there is much I can draw out of this theological premise that you haven’t read or thought.

But there is an aspect of this passage that I’d like to point out that you may not have thought of, may not have read. It seems really important to me that Paul assigns righteousness “not only to the adherent of the law but also to the one who shares the faith of Abraham.” He includes among the righteous the adherent of the law. The Greek doesn’t really say “adherent.” It says, “the one out of the law,” or “from the law.” That says to me that Paul is less concerned with the acts of obedience to the Law than the identity that flows from the Law of Moses. It is almost as if the one whose identity flows from the law is its descendent, as are believers descendents of Abraham.

But Paul goes further here, describing Abraham as “father of us all.” This is a marked departure from the way he uses Genesis 15 in the letter to the Galatians. In that letter Paul points out that the promise is to Abraham’s “seed” in the singular, which he interprets to mean Christ. So that the promise of Abraham’s seed skips the Jews and proceeds through Christ to those who share His belief. In several other ways Galatians excludes the Jews from God’s promises and extends them solely to “Christians.” (I find myself reluctant to differentiate too clearly between Jews and Christians in the first century as these identities were so much more muddled than we view them today.)

In Romans this apparent rejection of the Jews is abandoned (thankfully). How do we account for this change? It could be that Paul’s theology regarding his own people has changed, but I don’t think that’s it. It is much clearer if we keep in mind the central purposes of each letter. In Galatians Paul is writing to a Gentile congregation to adjure them to reject the demands of some (likely Jewish proselytizers, though many commentators think they are Jewish Christians) to accept circumcision. His opponents are Jewish and his audience is Gentile. His rhetorical purpose is to help the congregation in Galatia to stand up against Jewish pressure, and so his interpretation of Genesis 15 is shaped to fit that situation.

In Romans Paul’s primary concern is to change the behavior of the largely Gentile congregations toward the Jewish people under whose protection they still worship. (Keeping in mind the singular exception to the emperor cult that was given to the Jews by the empire.) He is not setting one set of beliefs against the other as he was doing in Galatians. He is doing three things here. First, he is grounding the faith of the Roman Christians in their Jewish roots by linking them to Abraham, “the father of us all.” Next I think that he is building up the faith of the Gentile believers here because he is going to require something difficult of them later in the letter (treating their Jewish siblings with greater respect). He affirms their standing before God so that when he demands that they change their behavior toward their Jewish siblings, he will have established trust on which they can lean. And finally, he reframes his Galatian arguments about Genesis 15 so that both Jew and Gentile are included.

So the argument of “righteousness through faith” is far more contextually nuanced than it sounds on the bumper sticker, “through faith alone.”

Gospel Text

Two weeks ago we read the story of the Transfiguration as Epiphany came to a close. That reading began with “And after six days.” This week we get the text that those six days came after. Just before our reading this week Jesus asked His disciples, “And who do you say that I am.” Peter replied, “You are the Christ.”

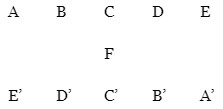

No sooner does Peter get these words out of his mouth than Jesus begins to teach about His crucifixion. No praise for Peter, no building the church upon a rock. “You are the Christ,” then “And I’m going to die.” I’ve written in the past weeks about the large structure called a “chiasm” that Mark has used to organize his Gospel. Elements from the first half are linked to matching elements from the last half, each transformed as it passes through the center.

(Except in Mark there are at least 8 pairs)

If you connect the pairs it makes an “X.” Chi is the Greek letter X, which is how chiasm gets its name.

And the center of Mark’s big X? Today’s reading. This is the spindle on which the entire Gospel rotates. Jesus’ explanation of the necessity of His death and, to a lesser degree, Peter’s initial rejection of it. Last week we noted that Jesus’ opponents in Mark are mostly semi-divine, demonic characters. They are replaced by human ones in the second half. Satan tests Jesus in chapter one, the authorities test Jesus in chapter 12. They take Satan’s place. I don’t think it’s accidental that Peter is called “Satan” after rejecting Jesus’ explanation of His pending death. Of course Peter isn’t Satan, but he gives voice to the enemy’s ideas.

And Jesus goes on to teach about what it will mean to accept the truth of Who He Is. The same fate awaits many who will choose Him. This is especially important in view of what I believe to be the purpose of Mark’s Gospel (as we have it), to prepare persons for baptism. The central question is, “Will you accept a Crucified Savior?” followed closely by, “And will you accept that you do this at the risk of your life?” Because I date Mark some time after the destruction of the Temple in 70, I cannot attribute this risk to the Neronian persecution (around 68). Still, Christian faith meant the rejection of the emperor cult and the risks that rejection entailed.

These risks then help me make sense of what Jesus says going forward. He speaks of those who would save their lives while actually losing them, those who lose them only to save them. I changed “life” and “soul” in the translation to “life/soul” because it’s all the same word, psyche. Going back and forth (as the ESV does) makes no sense. The word can carry both meanings, but here I do think that “life” works better in every instance. Especially in light of Jesus’ admonition about being ashamed of Him and His words.

It is the social function of shame that I would point to. In mimetic theory (Rene Girard) shame is a precursor to being set apart for sacrifice. Shame is fear of being seen as “different” in a way that marks the different one as a likely scapegoat. To be ashamed of Jesus and His words is to be afraid of being marked for death. Interestingly, Jesus speaks of the shame of the Son of Man at His return, too. And are not those who were ashamed of Him and His words at least part of the reason that He was marked for death?

These closing verses of this week’s Gospel are not a prediction of Jesus’ displeasure at His return. They are a description of the deadly consequences of our failure to accept fully the Messiah whose greatest gift to us is His life given on the Cross, a life we are called to emulate.

I can’t close this Divergence without noting what I see as a parallel to being a Christian today. A cult of “Christian” Nationalism has grown up that preaches the militant Christ that the Baptist preached and Mark’s Gospel rejects. The call on every Christian is to proclaim a Christ who will die rather than kill, and the cost of that proclamation seems to be growing.

For a more easily printable version of this Divergence, please CLICK HERE.