First Reading

1 Samuel 3:1–10 (11-20)

Now the boy Samuel was ministering to the LORD in the presence of Eli. And the word of the LORD was rare in those days; there was no frequent vision.

At that time Eli, whose eyesight had begun to grow dim so that he could not see, was lying down in his own place. The lamp of God had not yet gone out, and Samuel was lying down in the temple of the LORD, where the ark of God was.

Then the LORD called Samuel, and he said, “Here I am!” and ran to Eli and said, “Here I am, for you called me.” But he said, “I did not call; lie down again.” So he went and lay down.

And the LORD called again, “Samuel!” and Samuel arose and went to Eli and said, “Here I am, for you called me.” But he said, “I did not call, my son; lie down again.” Now Samuel did not yet know the LORD, and the word of the LORD had not yet been revealed to him.

And the LORD called Samuel again the third time. And he arose and went to Eli and said, “Here I am, for you called me.” Then Eli perceived that the LORD was calling the boy. Therefore Eli said to Samuel, “Go, lie down, and if he calls you, you shall say, ‘Speak, LORD, for your servant hears.’” So Samuel went and lay down in his place.

And the LORD came and stood, calling as at other times, “Samuel! Samuel!” And Samuel said, “Speak, for your servant hears.”

(Then the LORD said to Samuel, “Behold, I am about to do a thing in Israel at which the two ears of everyone who hears it will tingle. On that day I will fulfill against Eli all that I have spoken concerning his house, from beginning to end. And I declare to him that I am about to punish his house forever, for the iniquity that he knew, because his sons were blaspheming God, and he did not restrain them. Therefore I swear to the house of Eli that the iniquity of Eli’s house shall not be atoned for by sacrifice or offering forever.”

Samuel lay until morning; then he opened the doors of the house of the LORD. And Samuel was afraid to tell the vision to Eli. But Eli called Samuel and said, “Samuel, my son.” And he said, “Here I am.” And Eli said, “What was it that he told you? Do not hide it from me. May God do so to you and more also if you hide anything from me of all that he told you.” So Samuel told him everything and hid nothing from him. And he said, “It is the LORD. Let him do what seems good to him.”

And Samuel grew, and the LORD was with him and let none of his words fall to the ground. And all Israel from Dan to Beersheba knew that Samuel was established as a prophet of the LORD.) (ESV)

Second Reading

2 Corinthians 4:5–12

For what we proclaim is not ourselves, but Jesus Christ as Lord, with ourselves as your servants for Jesus’ sake. For God, who said, “Let light shine out of darkness,” has shone in our hearts to give the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ.

But we have this treasure in jars of clay, to show that the surpassing power belongs to God and not to us. We are afflicted in every way, but not crushed; perplexed, but not driven to despair; persecuted, but not forsaken; struck down, but not destroyed; always carrying in the body the death of Jesus, so that the life of Jesus may also be manifested in our bodies. For we who live are always being given over to death for Jesus’ sake, so that the life of Jesus also may be manifested in our mortal flesh. So death is at work in us, but life in you. (ESV)

Gospel Text

Mark 2:23-3:6

One Sabbath he was going through the grainfields, and as they made their way, his disciples began to pluck heads of grain. And the Pharisees were saying to him, “Look, why are they doing what is not lawful on the Sabbath?” And he said to them, “Have you never read what David did, when he was in need and was hungry, he and those who were with him: how he entered the house of God, in the time of Abiathar the high priest, and ate the bread of the Presence, which it is not lawful for any but the priests to eat, and also gave it to those who were with him?” And he said to them, “The Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath. So the Son of Man is lord even of the Sabbath.” (ESV)

Again he entered the synagogue, and a man was there with a withered hand. And they watched Jesus, to see whether he would heal him on the Sabbath, so that they might accuse him. And he said to the man with the withered hand, “Come here.” And he said to them, “Is it lawful on the Sabbath to do good or to do harm, to save life or to kill?” But they were silent. And he looked around at them with anger, grieved at their hardness of heart, and said to the man, “Stretch out your hand.” He stretched it out, and his hand was restored. The Pharisees went out and immediately held counsel with the Herodians against him, how to destroy him. (ESV)

Comments and Questions for Discussion

First Reading

In a recent Divergence (Trinity Sunday) we had the “call” of Isaiah, and it was noted that commentators suggest that this was not at all a call like that of the other prophets. Ezekiel, Jeremiah, Moses were all initially reluctant, and were given messages of warning to carry. Isaiah volunteered, and wasn’t really given a message at all, but told to deafen the ears, harden the hearts of the people so that they would not listen or understand. It was suggested that this vision of Isaiah’s was in fact from later in his ministry, when his message had fallen on deaf ears, and he came to understand that this lack of hearing resulted from God’s doing.

Samuel’s call in our reading for this week conforms more closely in some ways to the norm. He is certainly given a message of judgment to carry that he is reluctant to share. His failure to comprehend that it is God who is speaking might be seen as a parallel to the other prophets’ reluctance to take up the mantle of prophecy. The difference may be the result of his youth. Rather than resisting God’s call to prophesy, he just isn’t prepared to understand what’s happening. His initial reluctance to share what he’s heard with Eli the next morning makes me think that if he’d understood from the first, he would also have resisted from the first.

“And the word of the Lord was rare in those days.”

This also seems to contribute to Samuel’s failure to realize what he’s hearing, Who he’s hearing. People had grown accustomed to hearing infrequently from God, so young Samuel had no frame of reference for what he was hearing. God spoke, but the boy couldn’t believe that he’d been selected to hear from God, let alone speak on God’s behalf.

It was that reality that made me think, “Oh, yes, rather like today.” People are so unaccustomed to thinking that God speaks in the here and now that when they do hear Them speak, they attribute what seems a thought, or an impression, to something else. On the other hand, we hear others speaking in God’s Name in a way that bears no relationship to the God we know in Jesus, so we’re distrustful of the very idea of speaking out in this way, just as reluctant as Jeremiah or Moses to make fools of ourselves by sharing publicly what God has said to us in private.

“And the word of the Lord was rare in those days.”

I wonder how many others, ministering to God as Samuel was as a boy, had heard God call, and refused to believe, or more likely, to share what they’d heard with Eli? Was the word of God rare because God failed to speak? Or because we were old enough to understand the consequences of speaking out and decided not to?

The message of Jesus, that we are redeemed and beloved of God regardless of who we are, what we’ve done, that we are all “saved” by Jesus’ sacrifice on the Cross, that message is scandalous, and one that God desperately wants heard. We have all been indwelt by the Spirit and empowered to speak the word of God in this day. We’re not used to listening so that we can hear God’s specifics for the moment, just as Samuel wasn’t used to listening, but God is speaking. In Samuel’s day, Holy Spirit worked through relatively few individuals, but since Pentecost that trickle has become a flood of graceful words entrusted to all of us who know Jesus. All we need is to be encouraged to say, “Speak Lord, for your servant listens.”

Second Reading

Our reading this week from 2 Corinthians begins a series of lections chosen from that letter that we’ll encounter in the coming weeks, so it seems appropriate to begin here with something of an introduction to the letter as a whole.

In 1 Corinthians we see Paul wrestling with a troublesome congregation, one that is overly proud of its own spiritual gifts and overly impressed by rhetorical skill. The scene has shifted significantly by the time of 2 Corinthians. New challengers, preachers of a gospel quite different from Paul’s have entered the arena. To be faithful students of the letter, there are two questions I think we need to address, 1) the unity of the letter (which is often denied) and 2) just who the opponents are and what their different gospel is.

As an interpreter of 2 Corinthians, I will challenge to widely held assumptions about the letter. First, that it is actually a “composite” letter, made up of several fragments from other letters and second, that the opponents with whom Paul is concerned in the letter are super-pneumatists, (my word) that is persons whose qualification rests on their extraordinary experiences of the Holy Spirit. Both these understandings are those that I learned in seminary, and almost taken for granted by commentators on 2 Corinthians.

When I first studied 2 Corinthians, and even when I taught this letter early on, I accepted that the significant shifts in focus and tone in Paul’s second letter to Corinth signified that parts of it had been written at different times, in response to several letters he’d received. This may be a subject of interest to you, especially as it’s still so often asserted, but explaining that is beyond the scope of this short introduction. Let it be enough to say that a recent rhetorical analysis of the letter (LINK) has convinced me that it can, in fact be read as a unity. A complex unity, but a unity nonetheless.

The second advantage of 2 Corinthians as a unity is that it relieves us of the difficulty of imagining a copyist who took fragments of several letters (the number of imagined letters varies among scholars) and forced them into a whole like someone taking mismatched jigsaw puzzle pieces and pressing them together to the detriment of the parts and the whole. Yes, reading 2 Corinthians as one complex argument requires greater rhetorical dexterity, but I think it’s more faithful to the letter and to Paul.

The other commonly held view of 2 Corinthians is that the new missionaries to Corinth that Paul opposes were those who claimed superiority based on the quality and quantity of their spiritual revelations. These “super-apostles” challenged Paul’s teaching and threatened what he’d accomplished in the city in large part because they were so much more impressive than Paul had been.

The difficulty with this common understanding of Paul’s opponents for me are two. First, the basis for this image of them is based on a flawed methodology. Second, this understanding gives us little or no understanding of just what it was they preached or why it was so threatening to Paul.

In the first case, the construction of Paul’s opponents are super-pneumatists is based largely on what Paul says of himself. “If he argues from his own experiences of the Spirit, it must be because they had claimed greater for themselves,” the argument goes. This is neither necessary nor accurate. The method that yields this result is called “mirror technique,” but that method, applied according to its own rules, actually fails to define the opponents they way that interpreters have determined. Paul’s self-authorization by virtue of his spiritual experiences is not new here. We find the same in 1 Corinthians. And his later emphasis on Spirit in the letter apart from his own experiences can be well explained in another way. (I’ll get into that in more detail when we encounter it in our readings.)

In the second, some of Paul’s vitriol in the letter demands that we understand the content of the preaching of the “super-apostles” and what it was about that preaching that set Paul off so. While the vocabulary of 2 Corinthians may vary to some degree from that of Galatians, I now find it far more satisfying to read this letter as a response to Jewish missionaries whose “gospel” was one of a renewed covenant, rather than the “new covenant” Paul speaks of in the context of the Eucharist. This seems to me to draw the letter together and to give it much clearer purpose. Here’s a link to a second article on this new approach to Paul’s opponents. The references to “Spirit” in the letter (apart from Paul’s reference to his own spiritual experience) result from the relationship between the Spirit and the renewed covenant found in the Hebrew Scriptures. They do not speak to the self-authorization of Paul’s opponents.

Given all that, we then come to our portion of 2 Corinthians appointed for this week. These verses fall within what I’d call Paul’s argument from weakness. It seems likely to me that 1) his opponents do proclaim themselves (as opposed to Paul, “For what we proclaim is not ourselves, but Jesus Christ as Lord, with ourselves as your servants for Jesus’ sake.”) He then goes on to acknowledge his weakness and affliction in comparison to them, while declaring that this is a mark of his authority, not the lack of it.

Reading this portion of the letter with this context, it takes on new meaning. Paul isn’t writing about his affliction for no reason. It is directly related to the question of his authority among the Corinthians, which he defends before countering the teachings of the new missionaries who oppose him. It is why I keep harping on the necessity of reading every epistle as a contingent document. When we separate Paul’s missives from his purpose for them we can read all sorts of things into the text that aren’t there.

The kind of teaching these new super-apostles bring with them will become clearer as we read more of 2 Corinthians in the weeks to come.

Gospel Text

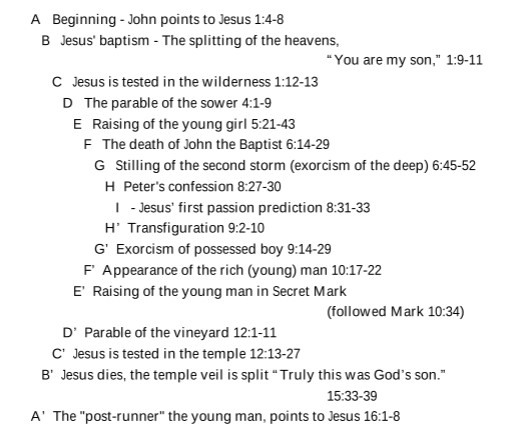

The text assigned from Mark for Proper 4 includes two of the five stories that make up the smaller chiasm within the Gospel of Mark. I have elsewhere pointed to the larger chiastic structure of the Gospel, but it was this smaller chiasm, combined with the widely accepted inclusio of the tearing of the heavens in chapter one and the tearing of the Temple veil in chapter 15 that led me to investigate the possibility that Mark had employed chiasm as a larger organizational tool.

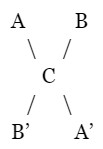

Chiasm, as a literary form, is something that when diagrammed, looks like an X. You have a statement or story, “A” followed by “B,” then “C” then a slightly different story related to B, so “B’”, then another like A, “A’”. It looks like this

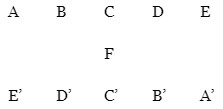

Chiasms can be more complex, like this diagram.

And in Mark we have a much more complex version, not written as an X, so that you can see how each pair is related.

This larger structure will pop up again and again later as we walk through Mark’s Gospel, but for the time being, we need to focus on the smaller one in chapters 2 and 3 that includes our stories for Proper 4. These two controversy stories are the B’ and C’ of the smaller, five part chiasm. In a chiasm, the center, the “C” is the most important element, transforming the first legs of the X into the second legs. It is the “crux” (the play on the word for “cross” is intentional) of the argument, and the crux of this argument is Jesus prediction that the bridegroom would be taken away from the wedding guests, an allusion to His crucifixion. If you look back at the diagram of the whole of the Gospel above, you’ll see that Jesus’ prediction of His crucifixion lies at the center of that one, too.

The first of our two stories then is the twin of the controversy about Jesus eating with sinners, earlier in chapter two. And the second of this week’s stories is paired with the controversy of Jesus’ healing of the paralytic. And if we didn’t get the point of the set of five controversy stories grouped in this fashion, Mark makes it clear by concluding them all with, “The Pharisees went out and immediately held counsel with the Herodians against him, how to destroy him.”

The Cross lies at the heart of Mark’s Gospel, and it casts its shadow over these two stories about eating (kosher behavior) and healing (authority). As we work our way through Mark’s Gospel, I’ll try to make clear why I think this is because Mark intended to confront his readers with the question of whether or not they were willing to be baptized in the Name of a Crucified Lord.

For a more easily printable version of this Divergence, please CLICK HERE.